Forever Chasing the Shiny New Thing: Thoughts from a Long-time Biostatistician

There are new and exciting advancements in drug development all the time. In my 20+ year career, I’ve certainly seen and experienced many. However, despite these advancements, the overall efficiency of drug development really hasn’t seemed to improve much.

Often, we modify our approach to drug development for each new advancement expecting great results; but the reality is often disappointing.

Recent advancements include adaptive design, biomarkers, real-world evidence, electronic data capture, decentralized clinical trials, artificial intelligence, and machine learning, to name a few. Are these advancements simply just hype? Are we overselling them? If they do not truly add to the efficiency of the process, should we even implement them at all?

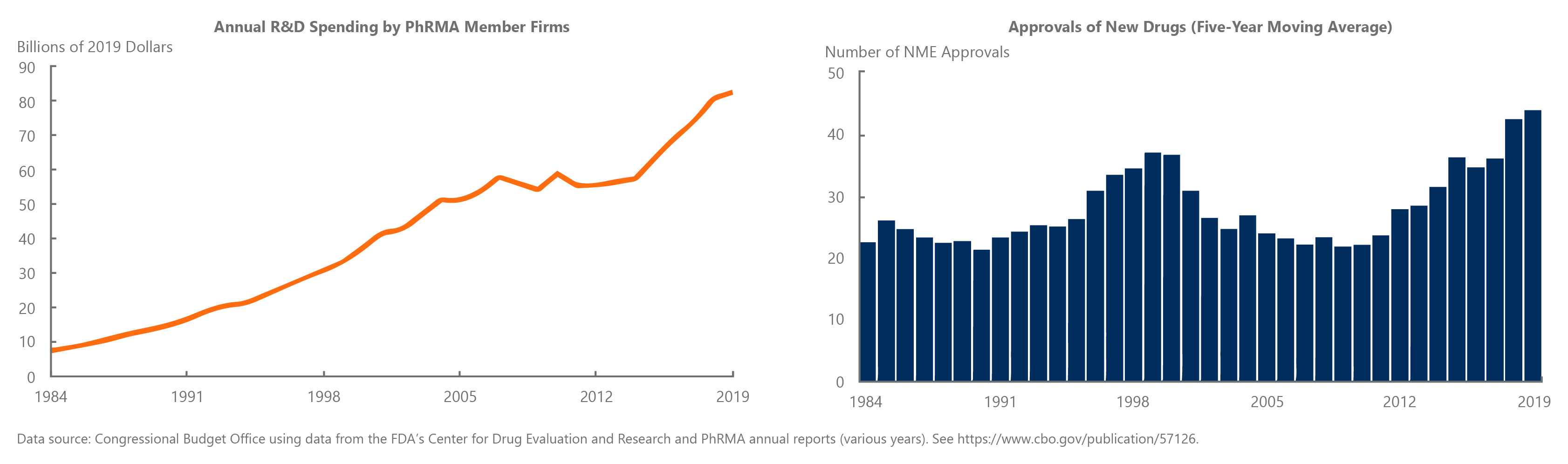

The graphs above show that increased spending in research and development do not necessarily lead to rising numbers of new drugs.1

Everything has a cost

Almost all new advancements come with a cost, in either the time needed to develop it, or the money required to acquire the data or technology.

If we try to utilize all the latest advancements at once, the monetary cost becomes overwhelming, not to mention the additional pressures on staff and other resources.

Everything looks like a nail

In my years of experience, it seems we keep trying to find the “next big thing” that will be the perfect solution for drug development. We tend to latch on to a technology and try to apply it to the entire portfolio. As the saying goes, “when all you have is a hammer, everything looks like nail.” We as an industry try to use the shiny new hammer to solve every “nail” problem.

Let’s take the time to assess each option

Instead, we should take the time to evaluate multiple approaches and technologies, assessing which one will be the most successful in accomplishing the end goal. We need to make sure we truly understand the pros and cons and implementation issues for each new advancement.

The best approaches and technology will vary based on disease area, product, stage of development, or even the company and its resources.

Real world evidence, for example, may be extremely useful in some disease areas but not so much in others. Even within the same disease indication, it might be more valuable in late-stage development in some cases and more valuable in early-stage development in others.

Another example is targeted therapies, which in some cases, is the only way to develop a product that demonstrates the type of benefit/risk that is reimbursable. However, when there’s not enough information known about the disease and/or Mode of Action trying to find a “magical subgroup” that a product could target may not be fruitful.

Even as universally used as approaches as electronic data capture (EDC) may not always be logical. Organizations often accept the cost of using EDC, but if you’re running a small study in a single site with elderly patients, a simple validated paper questionnaire may provide the same information with a significantly lower cost, depending on how the information will be used.

There is a cost associated with obtaining and utilizing data to make better design and development decisions. But unless you are operating in an environment with unlimited resources where you can try every approach possible, this is not the reality for most organizations.

Using the fit-for-purpose approach

We need to make sure to bring the right tool from the tool chest to provide better efficiencies.

We can do this by prioritizing the consideration of multiple approaches, by identifying the pros, cons, and tradeoffs for each.

We should always fit the strategy with the product and objective, so we can most effectively invest in the right resources to get the maximum “bang for your buck.”

Instead of chasing every shiny new thing, we need to use fit-for-purpose drug development strategies that may very well use those shiny new things, but in combination with those that may be more optimal but have the tarnish from age.

Our approach at MMS is to understand the objectives of each sponsor and then work to provide a fit-for-purpose solution that will be cost-effective and best suited to the situation at hand. We apply our expertise and experience specifically to the needs of individual clients and tailor our services to fit.

Our team of experts at MMS can also help your organization take an honest look at the shiniest of the new things to evaluate its fit-for your situation.

By: Kevin Chartier, Ph.D., Principal Advisor, Biostatistics and Submissions Planning

Learn more about MMS Biostatistics here.