Informed Consent in Clinical Research: Understanding its Significance and Sponsor Obligations

Informed consent serves as a safeguard to protect the rights and well-being of clinical research participants. While all legitimate clinical research follows ethical guidelines, conducting research involving human subjects requires an extra commitment to ethical principles, with informed consent as an essential aspect.

Pharmaceutical and biotech sponsors need to ensure that all participants fully understand the potential risks and benefits of a new therapy considering various factors, such as ethical obligations, regulatory requirements, data integrity, risk management, and public perception.

Throughout this article, we explore the significance of informed consent in clinical research, its principles, its process, solutions to challenges in obtaining informed consent, and the ethical responsibilities that it entails.

The Essence of Informed Consent

Informed consent is a process, not just another formality. Informed Consent is defined by the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) and Good Clinical Practice (GCP) as a process by which a subject voluntary confirms their willingness to participate in a particular clinical research study after having been informed of all the aspects of the study such as the study’s purpose, procedures, potential risks, and benefits that are relevant to the subject’s decision to participate.

This helps ensure that participants can make an informed and independent decision regarding their own involvement in a clinical study. It is an ethical and legal requirement for any research involving human subjects, and it is also a communication process between the clinical researcher and the participant.

If the participant is not capable of giving voluntary informed consent, the consent of a legally authorized representative (LAR) must be obtained.

Four main principles of informed consent in clinical research include:

- Information Disclosure: Participants should be given clear, understandable, and complete information about the study. This includes the study’s objectives, procedures, potential risks, benefits, and alternatives.

- Voluntary Participation: Participants should freely choose whether to participate or decline without coercion or pressure from the clinical researchers or any other party. They should be given the opportunity to ask questions freely and clarify all doubts.

- Competence: Individuals must have the capacity to understand the information provided to them to and make a rational decision. Special attention is given to vulnerable populations, such as minors and those with cognitive impairments.

- Continuous Consent: Consent is an ongoing process, and participants have the right to withdraw from the clinical study at any time without penalty.

Informed Consent Process (ICP)

Application of informed consent prior to any procedure follows the Informed Consent Process (ICP). This process is carried out as a systematic, regularized procedure mentioning and encompassing all essential components to be mandated in informed consent and to be followed where and whenever required.1

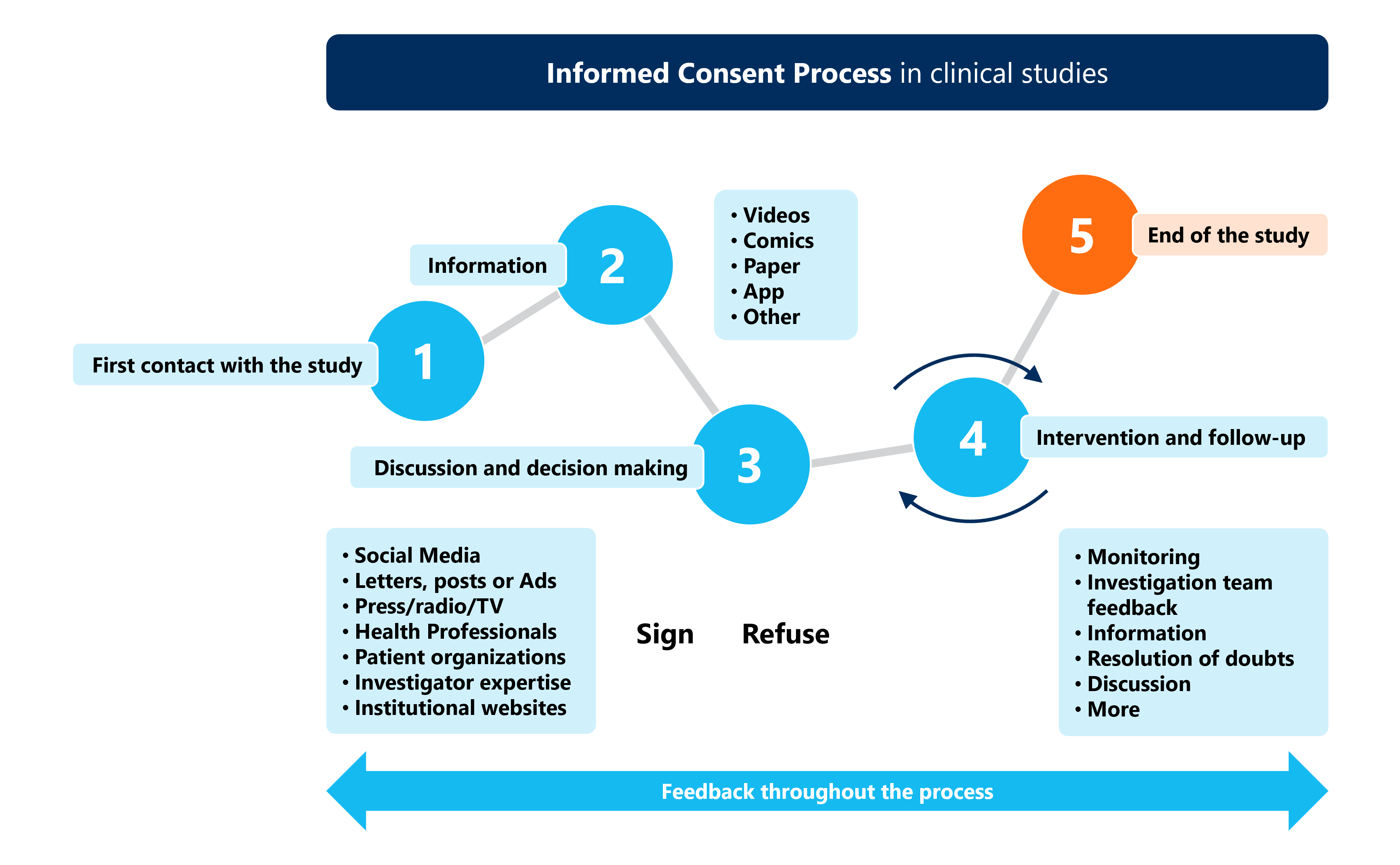

This process entails five different phases (as seen in Figure 1) from first contact through to the end of the clinical study. Most phases can be done either face-to-face or virtually, depending on what is considered most appropriate for the clinical study and target population.2

Figure 1: The five steps of the informed consent process in clinical studies.

Source: Guidelines for Tailoring the Informed Consent Process in Clinical Studies.2

Potential participants usually receive the Informed Consent Document (ICD), comprising the Patient Information Sheet (PIS) containing all clinical trial ‑related essential information in easily understandable language, and an informed consent form (ICF), to be signed by the subject and/or subject’s LAR confirming that they have been informed and verifying the subject’s voluntary participation in the study.

Alternative methods of obtaining informed consent should be discussed with the institutional review board (IRB), and Sponsors are welcome to contact the U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA) as needed for advice.3

Solutions to Challenges in Obtaining Informed Consent

Obtaining informed consent in clinical research can bring various challenges, but here are three ways for Sponsors to overcome common barriers, as follows:

- Complex Scientific Language: Communicating complex medical information in a comprehensible manner can be challenging, especially when dealing with individuals that have limited medical knowledge. Use of simple English language as well as translation into local languages is a recommended approach that is straight forward and easy to understand. Additionally, audio-visual tools have been documented to be useful in conveying informed consent information. Audio-visual tools enable immediate verbal reinforcement of written information, which aids in effective comprehension and recall.4

- Vulnerable Populations: Obtaining informed consent from vulnerable populations, such as children, the elderly, and those with serious illnesses, requires additional ethical considerations. In such cases, Sponsors should seek the LAR to make the medical decision and informed consent for that individual.

- Coercion and Pressure: Some participants may feel pressured to join a clinical study, particularly in situations where they believe it is their only option for treatment. This can be overcome by encouraging extended discussions between the investigator’s team and the participant for better understanding. These extended discussions can be conducted by investigators, nurses, clinical research coordinators, or medical social workers working with the study team after the actual consent process.

Ethical Responsibilities

In 1982, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) issued the International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects, also known as the WHO-CIOMS Guidelines.

These guidelines provide a framework for the ethical conduct of biomedical research involving human subjects, including the requirement for informed consent, and they detail how these universal ethical principles should be applied.5 Researchers and institutions conducting clinical research take on multiple ethical responsibilities concerning informed consent. This includes:

- Ethical Review: Ethical review boards play a crucial role in evaluating research protocols, including the informed consent process, to ensure compliance with ethical standards.3,6

- Informed Consent Documents: The Sponsor ensures that consent forms are written in plain language and any graphics are easy to understand.

- Obtaining Informed Consent: The Sponsor ensures that a valid informed consent is obtained for all subjects before recruitment and prior to carrying out any study specific procedures. Consent must be taken by the investigator or designated individual given approval/favourable opinion by the ethics committee. The Sponsor or investigator may delegate parts of the informed consent duties to appropriately trained and qualified members of the clinical research teams. The investigator must ensure that teams are adequately trained in clearly documenting the consent process in participant records and other trial related documentations according to guidance from the Sponsor.

- Ongoing Communication: The Sponsor or investigator should maintain open and honest communication with all participants throughout the study, addressing any questions or concerns promptly.

For Sponsors, effective implementation of an ICP requires clear, direct, point-by-point documentation for an easy understanding of the procedures concerned in research or clinical settings. Persuasiveness, respect for participants, working within ethical limits, and making use of extended discussions and the latest technologies, including audio-‑visual digitalization, all help augment the participation of individuals in research trials and therapeutic interventions.

Let us all work together to ensure that every participant is properly informed.

This article was written by Anju Bhakri, Senior Medical Writer at MMS. For further discussion on informed consent or medical writing support, please email info@mmsholdings.com and we’ll connect you with an MMS expert.

References:

- Chahal A. Informed consent process: challenges in clinical practice. Physiother Quart. 2022;30(4):27–29; doi: https://doi.org/10.5114/pq.2022.121145

- Guidelines for Tailoring the Informed Consent Process in Clinical Studies. I‑consentproject.eu (Funded by European Union H2020 programme)

- U.S. FDA, CBER, Informed Consent: Guidance for IRBs, Clinical Investigators, and Sponsors. August 2023, Good Clinical Practice

- Kadam RA. Informed consent process: A step further towards making it meaningful. Perspectives in Clinical Research 2017; 8:107-12.

- ICH E6 (R3) Guideline on good clinical practice, step 2b, 25 May 2023 EMA/CHMP/ICH/135/1995 Committee for Human Medicinal products.

- Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences. and World Health Organization. International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects. CIOMS; 2002. Available from: link